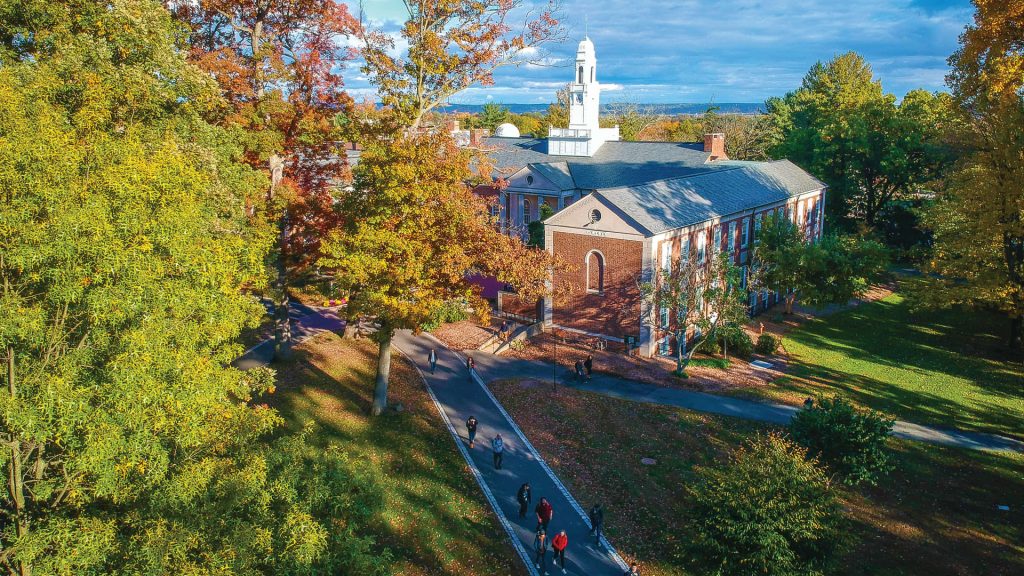

Drew University in Madison, N.J.

Courtesy: Drew University

As college and university leaders returned to campus this fall, there were new signs that a long-building financial crisis may finally be reaching a breaking point.

Closures and mergers are looming “at a pace we haven’t seen since the Great Recession,” said Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education.

The warning lights have been flashing for years. Fewer high school graduates are enrolling in college and the overall population of college-age students is shrinking, a trend experts refer to as the “demographic cliff.”

Higher operating costs and limitations on tuition increases have restricted institutions’ ability to raise revenue, according to 2024 research by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Higher education as a whole is “facing serious financial headwinds,” the report said.

And now, international student enrollment is poised to drop off due to the Trump administration’s tougher visa rules and anti-immigrant policies, representing billions of dollars in lost tuition and stripping away one of higher ed’s most reliable financial lifelines.

Add deep federal funding cuts, and the sector faces what Todd Wolfson, president of the American Association of University Professors, calls “a perfect storm.”

Collectively, with fewer students and less money coming in, there are fewer resources for teachers, programs, and most importantly, financial aid. For many schools, there may not even be enough funds to stay open.

International student enrollment is falling

Last September, the U.S. hosted more than 1.2 million students from abroad, an all-time high, according to the latest data by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

But in 2025, the number of international students on many U.S. college campuses is suddenly decreasing.

Largely due to the Trump administration’s recent changes to the student visa policy — which deactivated and then reactivated the immigration status of thousands of students and put a temporary pause on new visa applicants — there may be as many as 150,000 fewer international students enrolled for the 2025-26 academic year, according to preliminary projections by NAFSA: Association of International Educators.

That represents a 30%-40% drop in new students from abroad and a 15% decline in total international student enrollment, amounting to a loss of nearly $7 billion in economic impact, according to the findings, which are based in part on State Department data.

“International student enrollments are down massively,” said Wolfson.

Chris Glass, a professor and higher education specialist at Boston College, said the NAFSA analysis was in line with his own projection based on applications for F-1 student visas in the spring, which were trending lower even before the pause on new applicants.

However, new government data suggests that the total number of international students may not have declined to the extent NAFSA projected. “We just don’t know yet,” Glass said.

Drew University in Madison, N.J.

Courtesy: Drew University

At Drew University in Madison, N.J., about one-third of new students from abroad either withdrew or deferred this semester due to visa denials or lack of appointments, according to Hilary Link, Drew’s president.

“For a small institution like Drew, we did see an impact,” Link said. International students — coming from 58 countries around the world — account for 14% of Drew’s total enrollment of roughly 2,200 students, according to the school.

Fewer students, less revenue

Although international undergraduate and graduate students in the U.S. make up slightly less than 6% of the total U.S. higher education population, according to the Institute of International Education, they are an important source of revenue for schools.

U.S. colleges and universities need a contingent of foreign students, who typically pay full tuition, in addition to enhancing the diversity of perspectives in classrooms and on campuses, Mitchell said.

More from Personal Finance:

Trump administration to warn families about student debt risks

As colleges near the $100,000 mark, these schools are free

These college majors have the best job prospects

Altogether, international students who studied in the U.S. contributed $46.1 billion to the U.S. economy in the 2024-25 academic year, according to the most recent data by NAFSA, including tuition revenue as well as student spending, which extends well beyond higher education.

Those funds support colleges’ ability to provide financial aid, Mitchell said. “Full-paying international students pay scholarships for domestic students — it’s a 1-to-1 relationship.”

The colleges in jeopardy

When it comes to which colleges will be hardest hit, “it’s a tale of two worlds,” said Jamie Beaton, co-founder and CEO of Crimson Education, a college consulting firm. On one hand, “top schools are really bulletproof.”

In fact, Harvard University, which has been at the forefront of the escalating battle over international student visas, banked a recent win over the White House, freeing up $2.2 billion in grant funds.

The nation’s most elite colleges, including the Ivy League, have large endowments, a diverse student body and an advanced pipeline of applicants that largely shield them from sudden shocks. “They can fill their entire class over and over and over again,” Beaton said.

“These upper-tier schools are not without risk, but they have so many hedges against that risk they are more insulated from disruptions,” said Boston College’s Glass. “They are going to be the most resilient.”

Alternatively, “there is a fair percentage of institutions essentially living month to month, or paycheck to paycheck,” Glass said. Those less competitive and tuition-driven institutions are “extremely vulnerable,” he said. “International students have been integrated into their enrollment strategy and their viability.”

Mid-tier schools may also not be in the position to easily recruit other students, he added. “The pipeline is constricted, exposing them to risk.”

Some “will feel the immediate pain,” he said. Others “are going to bleed money, reallocate funds and see if they can survive.”

“It’s going to mean a lot of challenges for smaller, less wealthy institutions if the international student population declines and the domestic student population declines,” said Drew’s Link.

“We all need to work harder and more creatively to think about the value of a degree from a U.S. institution in this moment and how we make higher education more accessible and desirable,” Link said.

For decades, research has shown that getting a college degree pays: College graduates earn significantly more than those with just a high school diploma. But in addition to higher earnings and better employment prospects, getting a degree is the ticket to social mobility, allowing graduates from diverse backgrounds to climb the economic ladder — an opportunity that is unmatched elsewhere.

Yet, today’s pressures point to an era when fewer Americans go to college at all, and fewer colleges are in business.

“Declining international student enrollment is a piece of the larger puzzle undermining the financial health of higher education,” said AAUP’s Wolfson. “What we are going to see is programs shut down, campuses shut down, smaller public or private institutions closing or merging and a curtailment of opportunities for our students.”

For now, Mitchell said, “colleges and universities are not holding their breath” for a rebound in revenue. “They need to hit the cost side hard.”

Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas.

Courtesy: Southwestern University

“We are carefully monitoring all of our expenses, but we also know the next few years are going to be tough,” said Laura Trombley, president of Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. Only about 7% of the school’s 1,434 students come from overseas, she said, so the impact has been minimal, so far.

In times of financial stress, the first cuts would be to the facilities budget, Trombley said, followed by under-enrolled academic programs — often in the humanities — and then reducing the number of faculty and staff.

“You have levers to pull, but you don’t have that many levers,” Trombley said.