Starting this year, Washington state is imposing a new tax on credit unions that acquire banks. But critics say the levy will only succeed at driving such mergers out of the state.

Processing Content

“There’s no way one Banking Herald Reader of tax gets paid,” Mike Bell, an attorney who advises on credit union M&A deals at the Michigan law firm Honigman, told American Banker. “It will collect zero revenue dollars, and all it’s going to do is cause the market to perform without them.”

Washington’s state legislature passed the first-of-its-kind tax in the spring of 2025, and it took effect on Jan. 1 of this year. Under the new law, any credit union with a Washington state charter that merges with a bank governed by the state’s regulators must pay a business and occupation tax, to the tune of 1.2% of gross income.

The result, critics say, is that such mergers will no longer make financial sense, and local credit unions simply won’t undertake them.

“It’s being referred to as a tax, but in reality … it’s a de facto ban on the purchase of a state-chartered bank by a state-chartered credit union,” said Joe Adamack, head of legislative affairs at GoWest, a trade group for credit unions in Washington and five other Western states. “Realistically, this ceases that activity in the state for those specific institutions.”

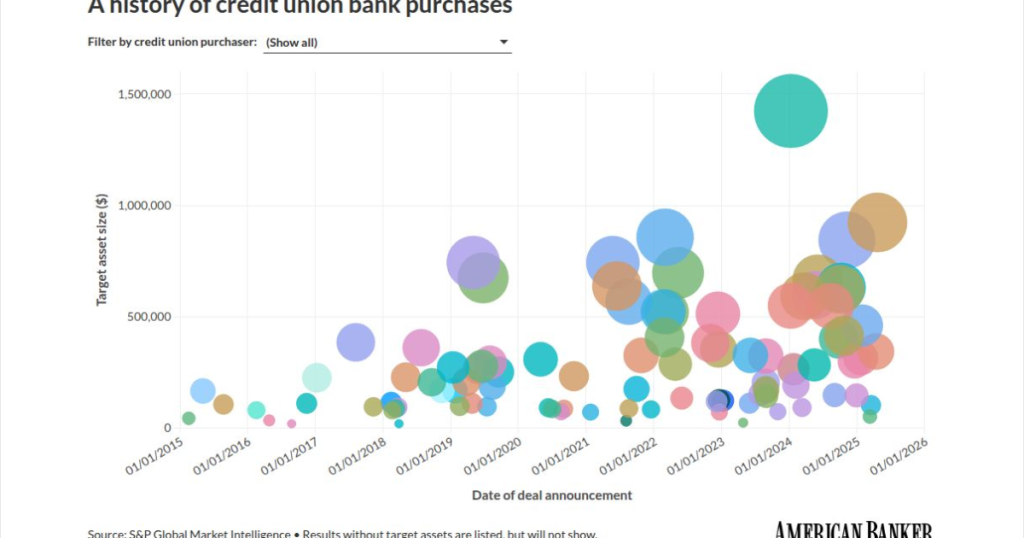

In recent years, credit unions have bought banks in record numbers. In 2024, there were an unprecedented

Bank industry groups have largely opposed these mergers, regardless of their effect on revenue. Just after the Zeal deal was announced, the Independent Community Bankers of America

The ICBA and other banking groups argue that credit unions, which are technically nonprofits, have an unfair advantage in the M&A market thanks to their exemption from a number of federal, state and local taxes. (Credit unions do, however, pay payroll and property taxes, among other categories.)

In addition, banks and their advocates say credit unions’ tax-exempt status means that when one acquires a bank, tax revenue decreases.

“When a credit union acquires a bank, state or local governments can lose much of the tax revenue that the bank was paying,”

As Washington’s new law took effect, local banks enthusiastically supported it.

“Community bankers welcome the Washington legislature’s move to recover lost revenue when a tax-paying community bank is acquired by a tax-exempt credit union,” Kathryn Swenson, president of the trade group Community Bankers of Washington, said in a statement.

Credit unions have responded with a question: How can a tax on acquisitions generate revenue if, thanks to that tax, the acquisitions stop happening?

When Washington’s legislators passed the tax on credit unions acquiring banks, they justified it partly as a way to help make up for a

“That ignored the fact that this would ultimately turn off that activity,” Adamack said.

Bell, who has advised on dozens of credit union-bank acquisitions, said he’s heard from his Washington clients that they would rather avoid such mergers than pay the new levy. With those buyers off the table, he expects the value of community banks in the state to take a hit.

“This choice, I believe, does have a material effect on the marketplace by removing a whole bevy of possible acquirers, which I think then lowers the value of any of those that sell,” Bell said.

Washington is not alone in seeking to crack down on credit unions’ acquisitions of banks. In both Mississippi and West Virginia, new laws require the entity acquiring a state-chartered bank to be insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., effectively ruling out credit unions.

In Washington, the new tax does include exceptions: According to

According to Bell, credit unions will adapt to these new rules — but not by paying the tax.

“All that will happen is the market will shift, and either out-of-state credit unions, federal credit unions, or others will buy these banks, or Washington state credit unions may convert to federal credit unions,” he said.

Meanwhile, GoWest says it’s still actively talking with Washington legislators as the law takes effect.

“I think we’ll see the impacts of this over the next six, 12, 18 months, and we’ll be responsive,” Adamack said. “This is not a finished conversation.”